김종길

먼 그림자, 혹은 현실의 배꼽

- 강경구의 미술현상학과 그 상징들

김종길 | 미술평론가

‘물의 상징’은 잠재적 가능성·근원성·형상 이전·창조적 힘의 원천·생명의 근원·풍요·치유·정화(淨化)·소멸·재생 등을 표상화(表象化) 한다.

_ 정진홍, 『엘리아데 종교와 신화』, 살림, 2003

물은 생명을 만들어내고 유지시키는 창조적, 생성적 바다이며, 살아 있는 물은 정체성이 담긴 물질, 영혼이 담긴 물질, 자아가 담긴 물질이다.

_ 베로니카 스트랭 지음, 하윤숙 옮김, 『물-생명의 근원, 권력의 상징』, 반니, 2015

이번 전시의 주제와 제목은 ‘먼 그림자’이다. 2010년 5월, 갤러리 스케이프가 기획한 개인전이 <먼 그림자>였고, 2011년 6월의 사비나미술관 전시도 <먼 그림자-산성일기>였다. 2008년에는 같은 이름의 작품 <먼 그림자>(캔버스에 아크릴 채색, 112.1×162.2cm)를 그렸고, 2011년에도 <먼 그림자>(켄트지에 목탄, 76×112cm)를 그렸다. 그에게 ‘먼 그림자’는 어떤 의미일까?

거룩한 하루

2003년 갤러리 피쉬에서 기획전 <다섯 사람 여행도>(7.16~7.29)가 있었다. 이 전시를 소개하는 글에 “다섯 작가가 2003년 2월 6일부터 22일까지 인도의 뭄바이, 아잔타, 조드푸르, 자이살메르, 바라나시 등을 여행한 후의 기록”이라고 적혀있다. 다섯 작가는 강경구, 안창홍, 김성호, 김을, 김지원이다. 강경구는 그 이전에도 인도에 간 적이 있을까?

인도를 방문한 뒤에(혹은 인도에서) 그는 스스로 깨달음(自覺)의 어떤 순간을 맞이한 듯하다. 그 이후 15년의 시간을 오롯이 ‘먼 그림자’의 세계를 궁구했고, 그것의 회화적 장면들을 그리고 있으니까.

그가 그곳에서 맞닥뜨린 깨달음의 실체는 무엇이었을까? 그때 그 하늘, 그 강, 그 시간, 그 사람, 그 주검들, 그 영혼들…. 어쩌면 그 순간들이 혹 ‘성현(聖顯, 성스러움의 현현)’과의 마주침이 아니었을까? M. 엘리아데는 성현을 ‘존재의 드러남’으로 바꾸어 말했다. 존재하는 모든 것이 스스로 존재한다는 것을 드러내는 것, 그것이 곧 ‘성현’이라고.

인도인들에게는 성현이 삶의 지루한 일상일 수도 있겠으나, 그가 마주한 갠지스강에서의 순간은 분명히 ‘다른 실재’였을 것이다. 그에게 그곳의 장면들은 그가 살아온 일상과는 완전히 다른 것이었기 때문에. 그러므로 인도에서의 나날은 그에게 그들과는 다른 하루로서 ‘거룩한 하루’였을지 모른다.

엘리아데는 성현을 삶 속에서 만나는 직접적인 실재라고 했다. 어떤 사물이 하나의 실존 주체에게 의미를 지닌 실재로, 곧 성(聖)으로 드러났을 때 그것은 실재이고, 거기 그것이 있어 그렇게 경험되는 것일 때 또한 그것은 의식의 현상이라고 말하기 때문이다. 다시 말하면, 성현은 ‘경험적 실재’이며 거룩한 것의 드러남이다. 그러므로 그가 ‘실재’를 깨닫게 된 순간의 하루는 거룩한 하루일 것이며, 그 하늘은 거룩한 하늘이요, 그 강은 거룩한 강이며, 그 시간은 거룩한 시간이었을 것이다.

그는 그 강에서 ‘먼 그림자’를 떠올리며, “현실과 피안의 세계를 종횡하는 수없는 영혼의 교차가 그들을 그토록 신념화시켰을까? 내세를 관통하는 정신적 힘이 그들을 그렇게 단단히 무장시켰을까?”를 의문했다(강경구, 「天竺國에서」, 2003. 평론을 준비하면서, 그가 쓴 이 글을 여러 번 정독했다. 짧은 에세이였으나, 2003년의 이후의 작품세계를 이해하는 좋은 실마리를 제공했다. 각 소주제별로 에세이의 부분들을 발췌해서 싣는다).

‘현실과 피안의 세계를 종횡하는 수없는 영혼의 교차’, 바로 그것이 그가 궁구하는 ‘먼 그림자’의 어렴풋한 실체라는 생각이다.

떠나가는 배에 가득한 영혼과 영혼들의 만남, 그 도도한 흐름들. 강은 꼭 그 강의 너비만큼 우리를 저들과 갈라놓는다. 다가설 수 없는 영혼들. 그들은 결코 우리를 거부하지 않지만 우리는 우리 스스로에 의해 거부되고 있다. _ 강경구, 「天竺國에서」, 2003

‘먼 그림자’의 첫 화두

‘먼 그림자’는 그림자가 멀리 있다는 뜻일 터인데, 그 의미를 밝히려면 그림자는 누구의 그림자이고, 왜 그림자는 멀리 있는 것인지를 살펴야 할 것이다.

2008년 학고재의 전시는 <강경구展>이었다. 그는 이 전시에 아크릴 채색으로 그린 <먼 그림자>와 <구름바다>를 출품했다. 벌거벗은 인물이 발목 깊이의 물에 들어가 가만히 물을 응시하고(아니면 사념에 잠겼거나), 또 뒷짐 지고 앉아서 어딘가를 바라보는 모습이다.

<먼 그림자>와 <구름바다>의 인물은, “흙으로 사람을 짓고 그 코에 생기를 불어 넣으니 ‘생령(生靈)’이 되었다”는 신화를 떠올리게 한다(창세기 2장). 왜냐하면 그 인물은 사람의 형상이지만 그의 몸은 온통 붉은 흙빛이기 때문이다. 그래서 그는 마치 ‘최초의 사람’처럼 보인다. 그런 그가 허리를 숙여 물속을 가만히 응시하고 있다. 물에 앉아서 구름바다를 보고 있다. 그가 바라보는 곳, 그러니까 ‘그림자’는 물속에 있거나 구름바다에 있는 게 아닐까.

수면(水面)의 안팎을 깊게 들여다보는 일은, 고대 샤먼들이 청동거울에 어린 먼 그림자를 찾는 것과 다르지 않다. 샤먼은 청동거울의 수면에서 과거를 꺼내어 해원(解冤)했고, 미래를 살펴서 기원했다. 그렇다면 ‘먼 그림자’는 우리 삶의 전경(全景)과 후경(後景)일 것이 분명하다.

눈앞의 현실을 전경, 눈 뒤의 현실을 후경이라 해보자. 전경은 생생한 삶의 현실이고, 후경은 그 현실에 맞붙은 현실 너머의 비현실/초현실의 세계일 것이다. 풀어 말하면, 우리 눈앞에 펼쳐진 현실이 전경이라면, 후경은 현실 너머에 있는 현실의 배꼽과 같은 그 무엇이다. 후경은 전경의 그림자와 같아서 보이지 않고 들리지 않으며 만져지지도 않는다. 신체의 감각을 내려놓은 자리에 영혼의 감각을 불 틔워야만 느낄 수 있는 그 무엇이라 할 수 있다(김종길, 「굿춤의 눈물, 환희, 그 소리들-조습의 해학적 카오스와 사진미학」, 2018).

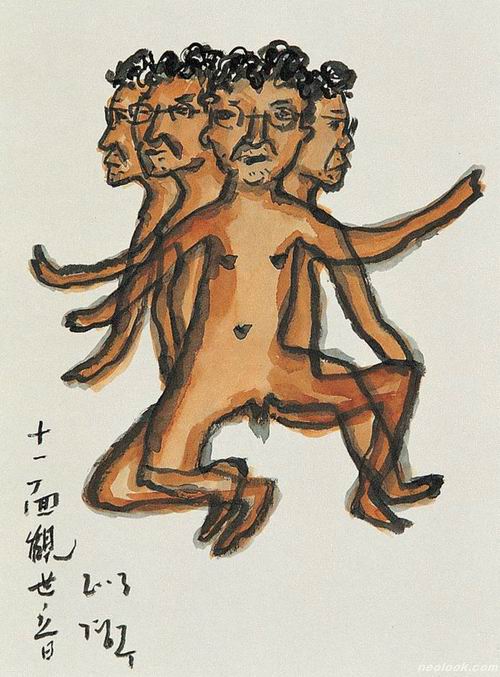

<먼 그림자>의 인물은 어떤 실체로서의 ‘누구’라기 보다는 존재의 원형과 같은 어떤 ‘추상(抽象)’이지 않을까? 강경구는 <다섯 사람 여행도> 전시에 자화상 <十一面觀世音>을 걸었다. 드로잉으로 그린 자화상은 벌거벗었고 그야말로 여러 얼굴과 여러 손을 가졌다. “스스로 존재한다는 것을 드러내는 것”의 표현이리라.

얼마 전에 작고한 시인 허수경은 “나는 마음이 썩기를 원한다. 오로지 몸만 남아 채취되지 않기를, 기록되지 않기를, 문서의 바깥이기를. 이것이 마음의 역사이다. 그 역사의 운명 속에 내 마음의 운명을 끼워 넣으려 하는 나는 언제나 몸이 아플 것”이라고 했다. 갠지스강에서 강경구는 불로 활활 타는 육신과 그 육신이 떠내려가는 강물을 보면서 그와 같은 생각을 했으리라. 문서의 바깥에서 마음의 역사로 남는 존재를 사유하면서, 추상같은 원형질의 존재를 떠올리면서.

그가 궁구해 온 15년의 ‘먼 그림자’는, 그 역사적 상상력은, 아니 그 신화적 상상력은 이승의 이 현실과 저승의 저 현실이 맞붙은 곳에서 생생화화(生生化化)로 피어난 풍경일지 모른다. 그는 그 풍경으로 잠입하기 위해 종종 <먼 길>(캔트지에 목탄, 2014)의 사내처럼 이승과 저승 사이를 흐르는 레테의 강을 건너는 것이고.

제 삼의 눈이었다. 그 눈은 양미간 그 어디쯤엔가 있어 그 곳을 통해 그들은 현세와 내세를 왕래하고 있었다. 시공간을 초월한 끝없는 허공 속으로 영혼의 간단없는 울림을 토해내고 또 감지해 내고 있었던 것이다. _ 강경구, 「天竺國에서」, 2003

다시 ‘먼 그림자’, 물의 씨알

강경구는 작년과 올해 ‘먼 그림자’ 여섯 점을 더 그렸다. ‘먼 그림자’에 딸린 부제는 <북서풍>(2018), <썰물>(2018), <바람소리>(2018), <역사의 시간>(2017), <운석>(2017), <아름다운 것들>(2018)이다.

그림 속에 등장하는 인물은 여전히 황토 빛의 ‘흙사람’이다. 첫 <먼 그림자>(2008)의 인물보다 더 강렬하다. 환한 흙빛으로 힘차다. 흙덩이 같기도 하고, 불덩이 같기도 한 인물을 보고 있으면 뜨거운 기운마저 느낀다. 그것이 생령의 ‘(뜨거운) 숨결’인지 아니면 활활 거리는 불의 심장인지는 알 수 없다. 그러나 그 몸이 불의 몸이요, 대지의 뜨거운 존재인 것만은 분명해 보인다.

가스통 바슐라르가 『몽상의 시학』(가스똥 바슐라르 저, 김현 역, 『몽상의 시학(기린총서 34)』, 기린원, 1989) 에서 “불들은 우리의 기억에, 아주 오래된 추억 너머에서 잠들어 있는 태고의 삶이 우리 속에서 그 불꽃으로 깨어나서, 우리의 비밀스러운 넋의 가장 깊은 나라를 우리에게 계시해줄 만한 힘을 행사한다.”고 했을 때, 바로 그 불꽃으로 깨어난 넋의 가장 깊은 곳을 생각할 뿐이다. 그런데 그 불의 이미지는 그의 작품에서 언제나 물과 더불어 현존한다.<먼 그림자-썰물>은 뜨거운 불/흙의 존재가 몸을 숙인 채 왼손으로 찬 물을 한 움큼 떠올려 보는 장면이다. 물을 가만히 응시하던 <먼 그림자>(2008)의 존재가 10년의 시간을 건너와 ‘물의 얼굴(水面)’을, 그 푸른 얼굴에 스민 먼 그림자를 슬쩍 떠 보는 것일 터. 물밀어 들었다 빠지는 썰물에서 그가 본 그림자는 무엇일까. 물은 근원이자 원천으로서 모든 존재 가능성의 저장소라고 엘리아데는 말했다. 또 물은 모든 형태에 선행하며 모든 창조를 받쳐줄 뿐만 아니라, 모든 창조의 모델이 되는 이미지는 물결 한 가운데 갑자기 나타나는 ‘섬’의 이미지라고도 했다. 반대로 침수는 형태 이전으로의 퇴행, 존재 이전의 미분화상태로의 회귀를 상징한다. 그러므로 물의 상징은 죽음과 재생을 모두 내포하고 있을 터(미르치아 엘리아데 지음, 이재실 옮김, 『이미지와 상징-주술적 종교적 상징체계에 관한 시론』, 까치, 1998. 참조).

엘리아데가 『이미지와 상징』에서 사유한 물의 상징은 강경구가 회화적 사유로 드러낸 물의 상징과 다르지 않을 것이다.

<먼 그림자-북서풍>은 불/흙의 존재가 숲으로부터 걸어 나오는 장면이다. 이 장면에서 숲은 숲 본래의 생태적 순환을 가진 생명으로 느껴지지 않는다. 그것은 어둠이요, 닫힌 세계이며, 탈주할 수 없는 경계선처럼 보인다. 그곳으로부터 불/흙의 존재가 물의 상징 속으로 걸어 들어오는 장면이랄까. 그는 지금 물결 한 가운데에 갑자기 성현으로 드러난 존재의 섬일 것이다.

<먼 그림자-바람소리>는 <먼 길>(켄트지에 목탄, 캔버스에 아크릴 채색, 2014), <먼 길>(목탄화, 2015)의 장면성을 그대로 잇는 작품이다. <먼 길>(아크릴 채색)이 불타는 하늘의 검은 바다를 건너는 푸른 존재라면, <바람소리>는 달빛이 짙게 깔린 물결을 헤치며 건너가고 있는 그림자 존재다. 그 존재는 몸의 균형을 잡듯이, 물을 거슬러 가듯이, 두 팔을 벌리고 상체를 앞으로 기울여 건너는 그의 뒷모습은 짙고 어두운 그림자이다. ‘검은 바다’는 늪과 같아서 잔물결조차 일지 않으나, ‘바람소리’는 달빛에 튕겨서 일어서는 푸른 물비늘을 타고 이편으로 실려 오는 바람을 느낄 수 있다.

그래서일까? 불현 듯 그의 그림자 뒷모습에서 ‘먼 그림자’를 본다. 처음에 나는 그림자가 ‘누구의 그림자’인지를 물었는데, 그것은 이제 바다의 그림자 같고, 역사의 그림자 같고, 신화의 그림자 같다. 그 ‘먼 그림자’는 그래서 남한산성이었다가 숲이었다가 별밤이었다가 부유하는 숱한 ‘가슴들’이었다가, 여행자가 된다.

강경구는 물속에 서 있는 네 명의 존재들을 그려 놓고 <꽃은 언제나 하늘 속에 있다>(2014)고 이름 붙였다. 그 존재들 여섯이 첫 <먼 그림자>처럼 무릎을 구부리고 허리를 숙여 물을 응시한다. 이번에는 <먼 그림자-아름다운 것들>이다. 하나에서 넷이 되고 여섯이 되는 그가 깨달은 것은 “물은 근원이자 원천으로서 모든 존재 가능성의 저장소”라는 인식이 아닐까.

그러면 물은 또 어디에서 왔을까. <먼 그림자-운석>은 물의 상징이 ‘운석’이라는 돌에서 비롯되었음을 암시한다. 그러나 이때 돌은 돌이 아니다. 그림에서 볼 수 있듯이 운석은 그의 ‘꿈꾸는 머리’(혹은 잠자는 머리)이다. 그러므로 운석은 물의 씨알을 품은 몽상의 시학이라 해야 할 것이다.

깊은 바다가 걸어왔네/ 나는 바다를 맞아 가득 잡으려 하네/ 손이 없네 손을 어디엔가 두고 왔네/ 그 어디인가, 아는 사람 집에 두고 왔네// (…) 바다가 안기지 못하고 서성인다 돌아선다/ 가지 마라 가지 마라, 하고 싶다/ 혀가 없다 그 어디인가/ 아는 사람 집 그 집에 다 두고 왔다//

_ 허수경, 「바다가」, 『내 영혼은 오래되었으나』(창작과 비평사. 2001)

현실, 기우뚱 거리는

<우러라 우러라> 연작은 여덟 점이다. 이번 전시에서 주목할 것은 ‘먼 그림자’의 세계에서 ‘우러라 우러라’의 풍경으로, ‘흐르지 않는 강’의 군상으로 전화(轉化)되고 있다는 사실이다.

‘우러라 우러라’는 「청산별곡」의 시어(詩語)이다. “우러라 우러라 새여 자고 니러 우러라 새여. 널라와 시름 한 나도 자고 니러 우니로라.”의 ‘우러라’는 현대어로 ‘우는 구나’ 또는 ‘울어라’이다. 이 시는 현실과 세속을 피하는 공간으로 ‘청산’과 ‘바다’를 그린다. 화자는 그곳을 동경하지만, 현실은 술로 시름을 달래거나 포기할 수밖에 없는 고려인의 삶과 비애를 노래한다.

강경구의 <우러라 우러라>는 「청산별곡」의 시적 비애를 공유하나 현실을 피하는 공간이 아니다. 오히려 그가 드러내는 회화적 풍경은 지극히 현실에서 비롯된 것이며, 역설적으로 그 현실적 풍경이 아이러니하게도 너무나 비현실적이었을 따름이다. 그가 그 풍경을 두고 술로 시름을 달래거나 포기하려고 했던 것은 더더욱 아니다.

그는 덕소 건너편의 새로 뚫린 춘천고속도로 아래 한강변에서 외래종 넝쿨식물이 강변 숲을 완전히 뒤덮은 장면을 목격했다. 덤불 그물을 씌워 놓은 듯 숲 전체를 장악하고 포섭해 버린 그 장면에 그는 소스라쳤다. 소름 돋는 경악이었다. 무어라 말로 표현할 수 없는 그 모습에서 그가 떠올린 것은 우리 현실이었다. 굳이 포스트 식민을 떠올리지 않더라도 우리 현실은 온갖 외래적인 것들로 뒤덮여 있지 않은가.

그는 그 장면들을 회화적으로 재구성하기 시작했다. 그 숲은 회화적 상상을 위한 실마리일 뿐이다. 그가 구상한 것은 외래종의 식물과 그 내부의 나무들을 마치 군상처럼, 살아있는 어떤 사물들처럼 배치하면서 ‘역설적 정황’을 표현하는 것이었다.

그것은 “역설이나 갈등으로 서술될 수밖에 없는 삶을 인식의 논리를 통해 해체하여 그렇지 않게 하는 것이 아니라, 그 역설과 갈등을 포함하는 전체적인 ‘구조’의 수용을 통하여 그러한 현실을 넘어서게 하는 것”으로서의 상징을 표현하고 싶었던 것이다. 그래서 그의 그림 속 덩어리들은 색채의 현란한 생동감으로 넘쳐날 뿐만 아니라, 그것들이 서로 견제하고 밀어내고 부딪히면서 ‘갈등’의 구조를 불러일으킨다.

심지어 푸른 색 군상들이 서 있는 것처럼 보이는 작품은 그들을 뒤덮은 넝쿨식물을 머리로 받아서 밀어내는 형국인데, 그 모습이 마치 어깨를 걸고 거리를 행군하는 시위대 같기도 하다. 또 비슷한 녹음 짙은 인물들의 군상은 하나하나가 기념비처럼 서서 기우뚱 거린다.

우리는 그들의 삶 속으로 결코 한 발자국도 다가설 수 없었다. 그들의 삶은 예측할 수 없는 어떤 계시에 의해 혹은 완고한 어떤 운명의 힘에 의해 지탱되고 있었다. 소위 21세기 문명사회의 일반적 사고로서는 도저히 가늠할 수 없을 것 같은 그래서 많은 우리의 예상을 엉망으로 만들어 버리는 그들이었다. _ 강경구, 「天竺國에서」, 2003

회색인, 멈추어 선 존재들

2003년의 기록에 “그 곳에는 시간이 흐르고 있지 않았다”는 표현이 있다. 그러면서 “무엇일까? 그들을 이끄는 힘은. 어떤 보이지 않는 실타래에 의해 조종되고 있는 듯한 사람들.”이라고 적었다. 그런데 흥미롭게도 그로부터 십 수 년이 지난 뒤, 우리 현실도 그와 비슷하게 흘렀다.

우리의 정치적 현실이 그랬고 그 현실을 벗어나지 못하는 사람들의 풍경이 이어졌다. 그 시간은 불가항력이었다. 흐르지 않는 시간은 고스란히 흐르지 않는 강과 다르지 않았다. 현실로 직립해 들어가는 회화가 아닐지라도 그의 회화는 늘 현실에 뿌리를 내리고 있었기에 그 풍경을 더듬기 시작했다.

<먼 그림자>, <먼 길>의 존재들이 찰랑거리는 푸른 물결을 걷고 서고 건넜다면, <흐르지 않는 강>의 존재들은 죽은 강가에 앉거나 서서 서성거릴 뿐이다. 흐르지 않는 강은 죽은 강이지 않겠는가. 그래서 색은 한 없이 무채색이고 사람들의 눈빛은 텅 비었으며 비스듬한 계단은 불안하기 짝이 없다. 게다가 각각의 사람들은 모두가 낱낱이다. 여럿을 그렸으나, 그 여럿은 홀로 여럿일 뿐이다. 고립이요, 고독이며, 소외이다.

이 작품과의 적절한 비교는 최인훈의 『회색인』일지 모른다. 1963년 6월부터 1964년 6월까지 『세대』에 연재한 소설이지만, 이야기 배경은 1958년 가을부터 1959년 여름까지다. 한국전쟁 이후 젊은이들이 겪는 갈등과 고뇌는 물론, 4.19혁명 직전의 우울과 전망을 동시에 보여주는 작품인 것. 무엇보다 당대 우리 사회의 모순과 부조리를 날카롭게 드러내면서 지적이고 비판적인 성찰을 담아낸 것을 기억할 필요가 있다. 소설 속에서 등장인물 독고 준은 현실로부터 스스로를 소외시키며 적응하지 못할 뿐만 아니라 상념의 시간들을 보내는 자신의 비겁함과 소심함에 끊임없이 갈등하는 인물이다. 강경구의 <흐르지 않는 강>의 인물들도 모두 ‘회색인’이다.

1958년으로부터 60년이 지난 2018년의 현실 또한 지난 두 정부를 살아야 했던 많은 사람들의 고뇌와 우울과 소외가 만만찮았다. 촛불 시민혁명 직전의 우울과 전망은 4.19혁명의 그것과 크게 다르지 않을 것이다. 강경구는 그때와 동일하게 모순과 부조리가 판쳤던 우리 사회를 성찰했다. 그리고 독고 준처럼 스스로를 소외시키며 현실에 적응하지 못하는 사람들을 보았다. 그들은 어디로도 흐르지 않았고 그래서 멈춰버린 존재들이었다. 전망 없는 시대의 존재론적 고뇌와 고통이 이어졌다.

다가설 수 없는 영혼들. 그들은 결코 우리를 거부하지 않지만 우리는 우리 스스로에 의해 거부되고 있다. 놀람과 충격과 경외감. 도저히 답변이 불가능할 것 같은 질문, 질문들. 그들은 도대체 누구이고 어디로 가고 있는가? _ 강경구, 「天竺國에서」, 2003

드로잉, 사유의 파편들

그의 드로잉은 한 편의 시적 조형물 같다. 깊게 생각한 뒤에 ‘한번 그음’으로 완성해 나간 드로잉들은 한 편 한 편이 하나의 서사를 구축했을 뿐만 아니라 그 자체로 놀라운 회화성을 획득하고 있기 때문이다.

물론 몇몇 드로잉이 <우러라 우러라>의 밑 작업처럼 보이기도 하지만 그렇다고 해서 부수적인 것으로 느껴지지는 않는다. 오히려 강렬한 색채를 드러내는 작품과 달리 흑연가루를 호방한 붓질로 붓춤을 추듯 칠해나간 드로잉에서 더 힘찬 골계미를 느낀다.

붓의 질감이 살아서 덧칠하고 덜 칠한 흔적들이 먹의 농담보다 더 생생하게 묻어나는 형국은 산세나 기세의 기운생동을 실감으로 끌어 올린다. 농묵(濃墨)이 짙게 배었으되 가장자리가 슬쩍 번지는 먹의 효과와는 비교할 수 없는 흔적들이다. 그러니 이 드로잉들에서는 ‘군상’이 아니라 겸재의 인왕제색이 먼저 떠오른다.

표암 강세황의 『송도기행첩』에 실린 ‘태종대’를 보는 듯, ‘영통동 입구’를 보는 듯, 그 그림들 속의 큰 바위를 큰 집으로 그린 듯한 드로잉들은 또 어떤가. 압도하는 덩어리들로 화면을 구성했으되, 얼기설기한 덩어리들의 배치에도 불구하고 꽉 짜인 균형은 그 어떤 회화보다도 일품의 멋이다. 게다가 그 덩어리들 속 어딘가에 빈틈의 창을 내고 인물을 그려넣은 꼴이 꼭 ‘매화초옥도’의 한 장면이다. 매화도 초옥도 없이 ‘매화초옥도’을 떠올리게 하다니!

첩첩산중인양 덩어리와 덩어리가 집과 집으로 첩첩을 이룬 장면들이기는 하나 그 사이를 비집고 들어선 창문과 작은 인물이 숨을 틔워서 첩첩을 연다. 나는 이 드로잉들에서 그의 작품 세계가 다시 진일보하는 어떤 세계로 넘어가고 있는 게 아닐까 하는 생각을 했다. 그가 그동안 보여주었던 ‘먼 그림자’의 세계는 물의 세계였고 물의 상징이었으며, ‘존재’를 질문하는 세계였다.

그런데 이 드로잉의 세계는 현실과 잇닿아 있으면서도 과거와 현재와 미래를 회통하는 사념적 세계관을 동시에 표출하고 있다. 건축용 ‘아시바’를 현실 세계의 위태로운 그물망으로 표현하기도 하고, 그 그물망이 다시 한 존재와 이어져서 나무가 되거나 의자가 되고, 실이 된다. 현실계와 상상계가 접경을 이룬 곳의 회화는 강경구가 이 세계에 던지는 새로운 상징언어다.

나는 그 언어에서 오래 누워 있었고, 오래 앉아 있었으며, 또 오래 서 있었던 미륵을 떠올리기도 한다. 운주사 와불과 금동 미륵 반가사유상과 바위처럼 서 있는 풍찬노숙(風餐露宿)의 미륵불들을. 하지만 그렇게 단정할 수는 없을 것이다. 아니 그렇게 단정해서도 안 될 것이다.

강경구의 사유는, 그 사유의 파편들은 드로잉으로 풀릴 때 너무도 자유로워서 그 세계의 현상학이 어디로부터 비롯되는지 알기 힘들어 보인다. 어쩌면 그 스스로가 ‘먼 그림자’여서 자신의 존재론적 고뇌를 풀어 헤치고 있는지도 모를 일이다. 그렇다면 그 고뇌의 시작은 그가 살고 있는 이 현실의 배꼽이지 않을까. 그 배꼽이 곧 중묘지문(衆妙之門)이고.

Shadow in the Distance, Or the Navel of Reality

- Kang Kyung Koo’s Art Phenomenology and Its Symbolism

Gim Jong-Gil | Art Critic

The “symbol of water” represents potential possibility, originality, pre-form, source of creative energy, origin of life, abundance, healing, purification, extinction, rebirth, etc.

_ Jeong Jin-hong, M. Eliade: Religion and Mythology, Sallim, 2003.

Water is a creative and generative sea, which makes and sustains life, and living water is matter containing identity, soul and ego.

_ Veronica Strang, Ha Yoon-sook trans. Water: Nature and Culture, Banni, 2015.

The theme and title of this exhibition is “Shadow in the Distance.” The solo show of the artist organized by Gallery Skape in May 2010 was titled Shadow in the Distance, and the exhibition at Savina Museum in June 2011 was also Shadow in the Distance: Mountain Fortress Diary. In 2008 the artist painted a work with the same title, Shadow in the Distance (acrylic on canvas, 112.1×162.2cm), and again in 2011, with charcoal on paper (76×112cm). So what is the significance of “Shadow in the Distance” to artist Kang Kyung Koo?

Sacred Day

In 2003, Gallery Fish organized the exhibition Journeys of Five People (July 16-29). The text introducing this exhibition says it was “documentations of travel by five artists to Mumbai, Ajanta, Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Varanasi, India, from February 6 to 22, 2003.” The five artists were Kang Kyung Koo, Ahn Chang-Hong, Kim Sungho, Kim Eull and Kim Jiwon. Had Kang Kyung Koo been to India before that?

After visiting India (or while he was still there) the artist seems to have experienced a certain moment of personal enlightenment. After all, he devoted himself to the world of “shadows in the distance” for 15 years thereafter, and continues to create such painterly scenes. What was the substance of the enlightenment he encountered there? The sky, the river, the time, the person, the dead, the souls... Perhaps those moments were in fact encounters with the “hierophany (manifestation of the sacred),” which M. Eliade refers to as the “revealing of the being.” Hierophany reveals that everything existing, exists on its own. Perhaps to Indians, incarnation of the sacred is a monotonous part of everyday life; however, the moment encountered by Kang at the Ganges River would definitely have been a “different reality.” Because the scenes there were completely different from his previous daily life, the days in India could have been “sacred days” for him, unlike the locals.

According to Eliade, hierophany is a direct reality encountered in life. That is because when a certain object is revealed to an existent subject as an existence with meaning, as something sacred, that is reality, and its presence and experience are phenomena of the conscious mind. In other words, hierophany is an “empirical existence,” and a revelation of the sacred. Therefore, the day holding the moment he became aware of the “existence” would have been a sacred day, as would the sky, the river and the time spent there.

Thinking of the “shadow in the distance” at that river, Kang wonders, “Was it the countless intersecting souls traversing the worlds of reality and the other side that gave them such conviction? Was it the spiritual force penetrating the afterlife that made them so strong?” Kang Kyung Koo, Thoughts in India, 2003. While preparing for this critique, I read this text by the artist many times. The short essay provided good clues toward understanding his world of art since 2003. Excerpts of the essay were cited to accompany each sub-theme.

“The intersection of countless souls traversing the worlds of reality and the world of enlightenment”―this must be the vague substance of the “shadow in the distance” pursued by the artist.

The encounter of souls and other souls filling the disembarking boats, the powerful currents. The river always separates us from them as much as the width of the river. Souls we cannot approach. Though they never reject us, we are being rejected by our own selves.

_ Kang Kyung Koo, Thoughts in India, 2003

The First Topic of “Shadow in the Distance”

To define the meaning of “shadow in the distance,” we must figure out whose shadow it is, and why it is in the distance. The exhibition at Hakgojae in 2008 was a solo show by Kang Kyung Koo. In this show, the artist presented Shadow in the Distance and Sea of Clouds, painted with acrylics. They were scenes of a naked figure standing in ankle-deep water and calmly looking into it (or in deep thought), or sitting with his hands clasped behind his back looking off into the distance.

The figures in Shadow in the Distance and Sea of Clouds remind us of the scripture “the Lord God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature.”(Genesis 2) That is because the figure is in the form of a human, but his whole body is the color of reddish earth. Thus he looks like the “first man.” The man is bending over to look down into the water. He is sitting in the water to look at the sea of clouds. So what he is looking at―the “shadow”―is perhaps in the water or in the sea of clouds.

Looking at the surface or into the depths of water is no different from the way ancient shamans searched for distant reflections in bronze mirrors. The shaman summoned the past from the surface of the bronze mirror to resolve grievances, examine the future and pray. If so, the shadow in the distance must refer to the foreground and background of our lives. Let us call the reality before our eyes the foreground, and the reality behind our eyes the background. The foreground is the vivid reality of life, while the background is the world of non-real/surreal, attached to reality but existing beyond it. That is to say, if the reality spread out before our eyes is the foreground, the background is something like the navel of reality, situated beyond reality. The background is like a shadow of the foreground―it cannot be seen, heard or touched. It is something that can be felt only if the senses of the soul are sparked in the place where one lets go of his physical senses. Kim Jong-gil, Tears, Joy and the Sounds of the Shaman Dance: The Humorous Chaos and Photo Aesthetics of Jo Seup, 2018.

Perhaps the figure in Shadow in the Distance is not “someone” specifically, but a certain abstraction representing the original form of being. Kang presented his self-portrait Eleven-Faced Goddess of Mercy at the exhibition Journeys of Five People. The drawing of the artist was naked, and literally had many faces and hands. This was no doubt an expression of “revealing the existence of the self.”

Poet Hur Soo-kyoung, who recently passed away, said “I want my mind to rot. So that my body will not remain to be collected, to be recorded, to remain outside documents. This is the history of the mind. Wanting to wedge the destiny of my mind into that destiny of history, my body will always be ill.” At the Ganges River, gazing at the bodies burning in flames as they drifted down the river, Kang Kyung Koo would have had similar thoughts. Contemplating on the being that remains as history of the mind, outside documents, he would have recalled the existence of the abstract-like primordial.

The historical imagination―no, the mythological imagination―of “Shadow in the Distance” pursued by the artist for 15 years is perhaps a landscape flourishing in growth, at a place where this reality of the present and that reality of the other world come into contact. It is to infiltrate into that landscape that the artist occasionally crosses the River of Lethe, like the man in Long Road (charcoal on paper, 2014).

It was the third eye. The eye was somewhere between the eyebrows, and through it they were travelling between this world and the afterlife. It was emitting the endless resonance of the soul into an endless void transcending time and space, while also sensing it.

_ Kang Kyoung Koo, Thoughts in India, 2003

Again the Shadow in the Distance, Seed of Water

This year and last, Kang painted six more Shadows in the Distance. The subtitles of these works were Northwesterly Wind (2018), The Ebb Tide (2018), The Noise of Wind (2018), Time of History (2017), Meteorite (2017) and Beautiful Things (2018).

The figures appearing in the paintings are still “earthen people” made in colors resembling red clay. They seem more intense than the figure in the first Shadow in the Distance (2008). They are powerful in their bright dirt-colors. Looking at the human figures, which resemble lumps of earth or balls of fire, one seems to feel a blazing energy. It is hard to tell, however, whether that is the “(hot) breath” of the living soul, or a heart of fire going up in flames. Nevertheless, it seems clear that the bodies are bodies of fire, and hot beings of the land.

As Gaston Bachelard said in Poetics of Reverie (La poétique de la rêverie), Gaston Bachelard, Kim Hyun trans. Poetics of Reverie (Girin Series 34), Girinwon, 1989.

“The fires are awakened within us as flames of ancient lives, sleeping in our memories, beyond very old reminiscence, exercising power strong enough to present a revelation to us on the most profound land of our secret souls,” we can only think of the deepest place of the soul awakened with that very flame. But that image of fire always exists together with water in his works.

Shadow in the Distance-The Ebb Tide shows the scene of the hot fire/earth-being bending over to dip a handful of cold water with his left hand. After crossing over a decade of time, the being in Shadow in the Distance (2008) is now gently trying to scoop up his “face of water,” the distant shadow cast on the bluish face. What is the shadow he saw in the ebb, as the tide came in, and then went out? Eliade stated that water, as an origin and source, is a repository of all possibilities of existence. Moreover, not only does water precede all forms, thus supporting all creation, but the image that serves as a model for all creation is the image of an “island” suddenly emerging in the middle of the water. Meanwhile, submersion symbolizes regression to a state prior to form, a return to the state of non-differentiation prior to being. Therefore, the symbol of water must include both death and rebirth. Mircea Eliade, Lee Jae-shil trans. Images and Symbols: Studies in Religious Symbolism, Kachi Publishing Co., 1998.

The symbol of water explored by Eliade in Images and Symbols would be no different from the symbolism of water revealed by Kang Kyung Koo in his painterly contemplation.

Shadow in the Distance-Northwesterly Wind is a scene of the fire/earth-being walking out of a forest. In this scene, the forest does not feel like a life form with its original ecological circulation as a forest. Rather, it looks like darkness, a closed world, a border that does not allow escape. It appears to be a scene of the fire/earth-being walking from that place into the symbol of water. The figure in the painting is now an island of being, who has suddenly been revealed in the middle of the water as a hierophany.

Shadow in the Distance-The Noise of Wind is a work that directly succeeds the scenes of Far Road (charcoal on paper, acrylic on canvas, 2014) and Far Road (charcoal drawing, 2015). While Far Road (acrylic painting) features a blue being crossing a dark sea under a burning sky, The Noise of Wind shows a shadow-being pushing his way across the moonlit waves. The rear view of the man crossing the water with his torso tilted forward and his arms spread out as if he were trying to keep his balance, working against the current, is portrayed as a dark shadow. The “black sea” is like a swamp and shows not the slightest ripple, but the “noise of the wind” can be felt as it comes this way, riding on the blue water scales, which seem to stand up to the tension of the moonlight.

Perhaps that is why I suddenly see the “shadow in the distance” in the back view of his shadow. At first I asked “whose shadow” it was, but now it seems to me it is the shadow of the sea, the shadow of history, and the shadow of a myth. Hence, the “shadow in the distance” was the Namhan Fortress, a forest, a starry night, countless drifting “hearts,” and then a traveller.

The artist painted four beings standing in the water and named this work Flowers Are Always in Heaven (2014). Six of those beings bend their knees to gaze into the water, as in the first Shadow in the Distance. This is the work Shadow in the Distance-Beautiful Things. Perhaps what he realized, as one became four and then six, was the perception that “water, as an origin and source, is a repository of all possibilities of being.”

If so, then where did water come from? Shadow in the Distance-Meteorite suggests that the symbol of water originated from the rock called the “meteorite.” But this rock is not a rock. As anyone can see in the painting, the meteorite is his “dreaming head” (or sleeping head). Therefore, the meteorite should be seen as poetics of reverie, incubating the seed of water.

The deep sea came walking./ I welcome the sea trying to grasp it in full./ I have no hands, I left my hands somewhere/ somewhere, I left them in the home of someone I know.// (…) The sea is unable to be embraced, and turns around after lingering./ Don’t go don’t go, I want to say/ but I do not have a tongue, somewhere/ I left everything in that home, the home of someone I know.//

_ Hur Soo-kyoung, “The Sea,” Though My Soul is Old, Changbi Publishers, 2001.

Reality, Swaying

The series Cry, Cry consists of eight works. A notable fact in this exhibition is that the world of “shadows in the distance” is being inverted into the landscapes of “Cry, Cry” and the groups of people in “A River That Does Not Flow.”

“Cry, cry” is a phrase from the old poem Cheongsanbyeolgok. The world “cry (ureora in old Korean)” in the verse, “Cry, cry, birds, cry after waking from sleep, birds. I, with more worries than you, cry after waking from sleep,” means “cry” or “you are crying” in modern Korean. The poem portrays the “blue mountain” and “sea” as spaces to seek refuge from reality and the secular world. The poet longs for these places, but in reality he sings about the life and sorrows of the Goryeo person, who can either soothe his worries with liquor or simply give up.

But while Kang’s Cry, Cry shares the poetic sorrow of Cheongsanbyeolgok, it is not a space to escape from reality. Rather, the painterly landscape revealed by him originates from utmost reality, though ironically, that realistic landscape was too unrealistic. By no means did the artist try to soothe his sorrows with alcohol or want to give up.

The artist witnessed a scene of a foreign species of vine completely covering the woods along the banks of the Han River under the newly built Chuncheon Expressway, visible from Deokso on the other side of the river. He was frightened by the scene of takeover and domination of the entire forest, as if it was covered with a net of creepers. It gave him a hair-raising shock. What came to his mind, impossible to put into words, was our reality. Not to mention post-colonialism, our reality is covered with all sorts of foreign things.

Kang began to recompose those scenes as paintings. The forest was just a clue for painterly imagination. What he thought of was to portray the foreign plants and the trees inside as groups of figures, arranging them like living objects to express the “paradoxical circumstances.” The artist “did not want to deconstruct the life that could only be described through paradox or conflict by the logic of perception, but wanted to enable transcendence of such reality through the accommodation of an overall ‘structure’ including the paradoxes and conflicts,” expressed as symbols. Thus the lumps in his paintings not only overflow with vivid colors of liveliness, but also create structures of “conflict” as they check, push against and collide with one another.

In work that appears to be a group of blue people standing, the figures seem to be using their heads to push away the vines covering them. The scene also resembles a group of protesters marching in the streets, with arms around each other’s shoulders. Meanwhile, figures painted green like the trees stand in a group like monuments, swaying.

We were unable to take a single step into their lives. Their lives were being maintained by a certain unpredictable revelation or a certain obstinate force of fate. It seemed absolutely impossible to judge them by the general way of thinking in the so-called 21st-century civilized society, which consequently made a wreck of our anticipations.

_ Kang Kyung Koo, Thoughts in India, 2003

Gray Men, Beings at a Standstill

In the artist’s records from 2003, there is the expression “Time was not flowing in that place.” He continues to write: “What is it... the power driving them. The people seem to be controlled by some invisible strings.” Interestingly, after more than a decade, our reality has flown in a similar way. This was an aspect of our political reality, followed by a landscape of people that were unable to escape from that reality. That time was beyond control. Time that does not flow is no different from a river that does not flow. Though it was not painting that addressed reality directly, his painting had always been rooted in reality, and thus began to grope for those landscapes.

While the beings in Shadow in the Distance and Far Road stood in, walked in or crossed the blue, sloshing waves, the beings of A River That Does Not Flow just sat or loitered on the dead riverbanks. After all, a river that does not flow is a dead one. Thus, the colors are utterly achromatic, the people’s eyes are empty, and the slanted stairs are disturbingly unstable. Every person is separate. The artist painted many, but the many are merely multiple singles. They are isolation, solitude and alienation.

Perhaps an appropriate comparison with this work could be A Gray Man by Choi In-hun. The novel, published as a series in Sede from June 1963 to June 1964, was based on a story that took place from the autumn of 1958 to the summer of 1959. It was a work that revealed not only the conflicts and agonies experienced by young people after the Korean War, but also the melancholy and prospects right before the April 19 Revolution. Above all, we need to remember that it sharply revealed the contradictions and irrationality of Korean society at the time, while providing intellectual and critical reflection. In the novel, Dokgo Jun is a character who not only alienates himself from reality, unable to adapt to society, but also experiences endless inner conflict over his passive and cowardly temperament, and spends time lost in his thoughts. All the figures in Kang Kyung Koo’s A River That Does Not Flow are also “gray men.”

The reality of 2018, 60 years after the year 1958, is also a time during which many people have experienced agony, depression and alienation, amidst the transition of governments. The melancholy and prospects prior to the candlelight revolution by citizens would have been no different from those of the time before the April 19 Revolution in 1960. Kang also has reflected on Korean society, with its prevailing contradictions and irrationality. And he saw the people alienating themselves, unable to fit into society, like Dokgo June. They were not flowing anywhere, and therefore were beings who had come to a standstill. The ontological anguish and suffering of an age without prospects continued.

Souls we cannot approach. Though they never reject us, we are being rejected by our own selves. Surprise, shock and sense of awe. Questions, questions that seem impossible to answer. Who are they, and where are they going?

_ Kang Kyung Koo, Thoughts in India, 2003

Drawing, Fragments of Contemplation

Kang’s drawings are like poetic sculptures. Each drawing, finished in “one stroke” after thinking deeply, not only constructs an individual narrative, but also gains amazing painterly quality in its own right. Of course some of the drawings look like underdrawings for Cry, Cry, but that does not make them feel subordinate. In fact, unlike the works that reveal vivid colors, the drawings in which the artist applies pigment with bold brush strokes as if he were doing a brush dance, present a stronger feeling of humorous energy. The texture of the brush comes alive so that the traces painted over and under-painted appear more vivid than the tones of ink, thus elevating the vital energy of the mountains or figures to a convincing level. These are traces incomparable to the effects of Korean ink, in which the stroke is dense while only the edges are slightly blurred. Thus in these drawings one is primarily reminded of Inwangjesaek by Gyeomjae, rather than a “group of figures.”

How about the drawings that appear as if they are portraying the large rocks in “Pyoam” Kang Se-hwang’s Songdo Gihaengcheop, or Yeongtongdong Entrance, in the form of large houses? The picture-plane is composed of overwhelming masses, but the well-organized balance, despite the arrangement of the entangled lumps, has a charm more elegant than any painting. Moreover, the way the artist opens an empty space somewhere amidst the masses to draw in a human figure is like a scene from “Maehwacho-okdo (Thatched House with Plum Blossoms).” He can make us envision “Maehwacho-okdo” without even any plum blossoms or straw-thatched house!

Though they are scenes consisting of layers and layers of masses and houses, little windows and small human figures create openings in between to make room to breathe. Looking at these drawings, I thought the artist’s world of art must be making a transition to a more advanced world. The world of “Shadows in the Distance” shown previously was a world of water, a symbol of water, and a world questioning “being.”

But this world of drawing expresses a world-view of personal thought penetrating past, present and future, while also maintaining connection with reality. The artist portrays scaffolding structures used for construction as precarious networks of the real world, which again connect with another being to become a tree, chair or thread. The painting of a place where the worlds of reality and imagination border one another is a new symbolic language presented to this world by Kang Kyung Koo.

I recall Maitreya, who lay for a long time, sat for a long time, and stood for a long time in that language. These are the lying Buddha in Unjusa, the Gilt-Bronze Maitreya in Meditation, and the other Maitreya Buddhas standing like rocks and enduring the wind and the dew. But I am not to make any conclusions. I should not make such conclusions.

The contemplation of Kang Kyung Koo, the fragments of that contemplation are so free when they are unraveled through drawing, it seems difficult to figure out where the phenomenology of that world comes from. Perhaps he himself is a shadow in the distance, trying to solve his ontological agonies. If so, the beginning of that agony would be the navel of this reality. And that navel would be the mysterious door of all exquisite principles.

FAMILY SITE

copyright © 2012 KIM DALJIN ART RESEARCH AND CONSULTING. All Rights reserved

이 페이지는 서울아트가이드에서 제공됩니다. This page provided by Seoul Art Guide.

다음 브라우져 에서 최적화 되어있습니다. This page optimized for these browsers. over IE 8, Chrome, FireFox, Safari